Columbus statues are coming down – why he is so offensive to Native Americans

Sam Hitchmough, University of Bristol

Over the past few weeks, statues of Christopher Columbus have been beheaded, covered with red paint, lassoed around the head and pulled down, set on fire and thrown into a lake. Many of these protests have been led by Native American activists. But other statues have been defended by people with guns.

California plans to remove a statue of Columbus from the state capitol building while others, including a famous statue in New York’s Columbus Circle are repeatedly debated.

In the wake of the killing of George Floyd, America’s multiple, entangled histories of racism are being thoroughly trawled in a search for the roots of ongoing prejudice. Planted deep within America’s psyche, one such root connects with the origin story of the nation itself: Columbus.

These recent attacks on statues and other figures associated with colonisation are part of a wider history of indigenous protests against longstanding settler narratives.

A contentious holiday

Columbus has endured as a particularly sacred national symbol. Despite the fact that the Italian explorer never set foot in what was to become the United States, he is lauded for “discovering” America and has been welded to the very idea of its modern nation state. In a speech marking Independence Day on July 4, the US president, Donald Trump, suggested that the “American way of life” began in 1492 “when Columbus discovered America”.

Columbus Day, originally on October 12, became a national holiday in 1937, energetically embraced by Italian-American communities as a badge of whiteness and acceptance in a nation that had been hostile to many Italian immigrants. Statues sprang up across the country, often donated by organisations such as the Sons of Italy. Columbus Day parades, some even predating the official holiday, featuring replica ships became commonplace, and Columbus increasingly became a symbol of courage and initiative, of pushing frontiers.

Presidents have lined up to praise his legacy. In 1988, Ronald Reagan suggested Columbus was the “inventor” of the American Dream, and in 2019, Trump hailed him as a “great explorer, whose courage, skill, and drive for discovery are at the core of the American spirit”.

Indigenous protests

Native American activists have long seen Columbus as a villain, an agent responsible for the invasion, conquest and subsequent occupation of the Americas. He represents the genesis of forces that embraced slavery and colonialism, because he was personally involved in enslavement, mass brutality and theft of indigenous land.

Today’s activists continue a longer tradition by Native Americans who have confronted US monuments. They have done so in ways that offer a counter-narrative that reveals hidden histories and gives voice to the silenced.

This Red Power activism by Native Americans has sought, often through symbolic acts, to achieve recognition of indigenous sovereignty and history, as well as decolonisation. At the height of Red Power movement protests in the 1960s-70s, activists occupied Mount Rushmore and protested on Thanksgiving Day at Plymouth Rock, seeking to contest these spaces of national memory and identity.

Protests against the Columbus Day holiday and parades, as well as commemorative statues, have continued to be regular occurrences – particularly since a programme of 500th anniversary events in 1992. The anniversary amplified Native American protests against what they perceived to be the celebration of genocide and conquest. Since then, anti-Columbus Day protests have gathered enough momentum for more than a dozen states including Hawaii, South Dakota and New Mexico to stop marking Columbus Day or else rename it Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

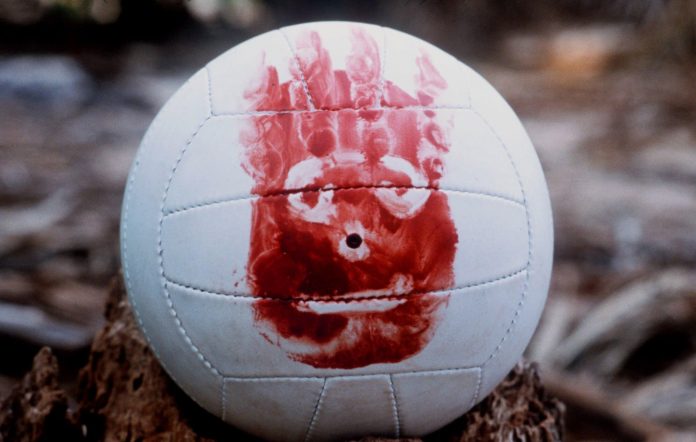

A common feature of protests in recent years has been pouring red paint onto statues of Columbus to represent the blood lost over centuries. Meanwhile, posters and banners read “Columbus = genocide” or “Our history is truthless, Columbus was ruthless”. In a 2007 Denver anti-parade protest, body parts of dismembered children’s dolls, symbolising brutality and murder, were strewn in front of the oncoming floats that recreated Columbus’s ships.

One-sided narrative

Many states are now voting to remove statues from state buildings and public parks, acknowledging the pain that celebrating Columbus causes for so many, and the way it privileges the settler narrative.

Statues of Columbus are markers of how societies choose to remember their history. It is a selective and often politicised process: who is chosen to be remembered and, equally, who is not. Physically pulling down a statue of Columbus does not erase him from history, it removes a symbol that publicly and officially celebrates a particular historical narrative. Many indigenous activists feel that bringing down the symbol of Columbus is an important challenge to a national narrative that continues to erase indigenous history as well as a way to forefront their own history.

In 2007, after years of being involved in anti-parade protests, leading Native American activist Glenn Morris told me in a research interview that the rejection of the racist philosophy behind Columbus Day may be the most important issue facing Indian country today. It is clearly no longer acceptable to nationally honour a man who represents a celebratory settler narrative that continues to ignore indigenous histories.![]()

Sam Hitchmough, Senior Lecturer in American Indian History, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.