Introduction

The Universe has many different centers as there are living beings in it. Each of us is a center of the universe, and hat universe is shattered when they hiss at you: “You are under arrest”.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn – The Gulag Archipelago

In the opening pages of his seminal work, The Gulag Archipelago, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn introduces us to a narrative that not only chronicles the harrowing depths of human suffering but also serves as a profound moral reckoning with the soul of a nation. This magnum opus, hailed as one of the paramount contributions to world literature, stands as an unflinching testament to the atrocities committed under the Soviet regime.

The Swedish Academy, in awarding Solzhenitsyn the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970, lauded the “ethical force” with which he imbued his exploration of the Russian people’s traditions. Mario Vargas Llosa, another luminary of literature, described Solzhenitsyn as “the man who described hell to us,” highlighting the stark realism with which he portrayed the Soviet gulag system. Similarly, Pilar Bonet referred to him as a “great voice” for shining a light on the shadows of Soviet society, and Mikhail Gorbachev acknowledged Solzhenitsyn’s pivotal role in eroding the foundations of the Stalinist regime.

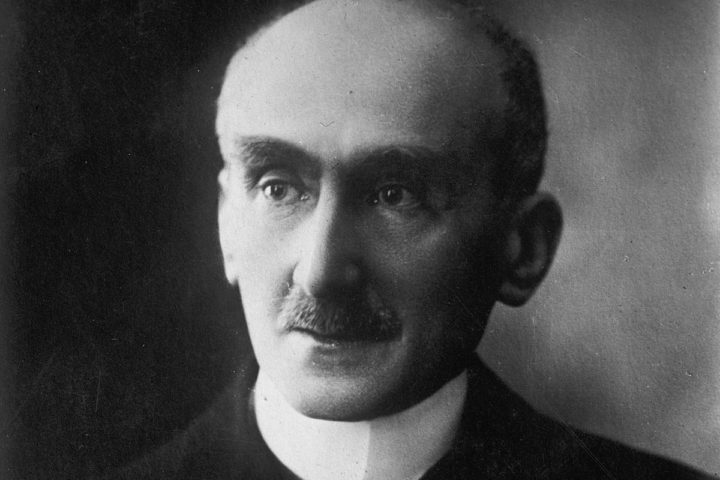

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: A Life Between Despair and Hope

Born on December 11, 1918, into the family of a teacher and a Cossack landowner, Solzhenitsyn embarked on a path that would lead him through the realms of physics and mathematics before thrusting him into the tumultuous waters of political dissent. His criticism of Joseph Stalin in private correspondence, deemed an act of treachery by the Soviet authorities, resulted in his arrest in 1945 and subsequent eight-year imprisonment. These years of torment and reflection fed into his later literary works, including Cancer Ward (1968) and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, the latter drawing directly from his time in the Ekibastuz forced labor camp.

Upon his release in 1953 and subsequent exile within the Soviet Union, Solzhenitsyn’s fortunes would briefly align with the political winds of change, leading to the publication of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich in 1962, under the aegis of Nikita Khrushchev. This period of relative openness, however, was short-lived, and Solzhenitsyn soon found himself once again at odds with the state, culminating in his expulsion from the Soviet Union in 1974, shortly after being awarded the Nobel Prize.

During his years of forced silence in the Soviet Union, Solzhenitsyn worked clandestinely on The Gulag Archipelago, a monumental narrative that would eventually be smuggled out of the country and published to international acclaim. This work, more than any other, cemented his reputation as a fearless chronicler of the human spirit’s endurance in the face of tyranny.

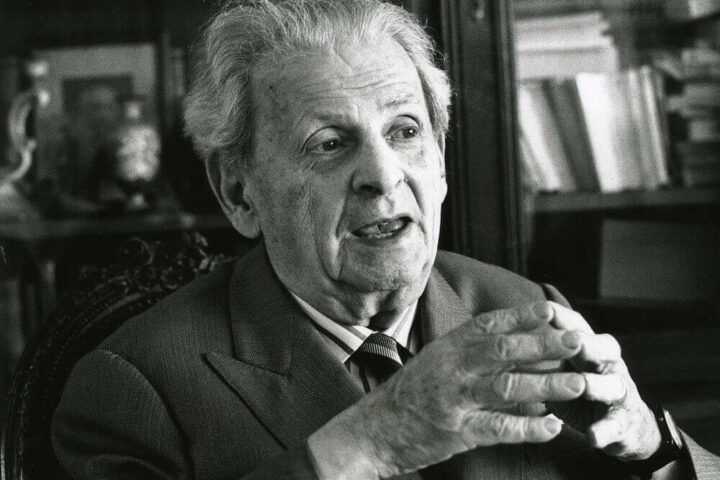

Solzhenitsyn and the Critique of Western Democracy

Upon his return to Russia in 1994, after a poignant exile of twenty years in the United States, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn embarked upon a chapter of introspection and profound critique, this time casting his discerning eye toward the West. His speeches and interviews from this period, notably his profound discourse at Harvard University in 1978, unveiled a critical perspective on Western civilization’s materialism and moral relativism. Solzhenitsyn, with his characteristic ethical intensity, dissected the spiritual and existential malaise he perceived at the heart of Western democracies, echoing the moral rigor with which he had previously exposed the tyrannies of Soviet rule.

At the venerable age of 87, and resettled in his homeland, Solzhenitsyn engaged in what the BBC described as “a strange interview” with Novedades de Moscú, wherein he lamented, “Western democracy is going through a serious crisis… This includes material and ideological support for the ‘colored’ revolutions, paradoxically advancing the interests of NATO in Central Asia.”

His seminal address at Harvard on June 8, 1978, stands as a critical examination of Western development in terms of culture, philosophy, politics, and its stance towards the so-called Third World. Solzhenitsyn challenged the prevailing belief that societies outside the Western sphere were merely hindered by tyrannical governance or crises from embracing Western-style democracy and living standards.

“There is this belief that all those other worlds are only being temporarily prevented (by wicked governments or by heavy crises or by their barbarity and incomprehension) from taking the way of Western pluralistic democracy and from adopting the Western way of life. Countries are judged on the merit of their progress in this direction. However, it is a conception which develops out of Western incomprehension of the essence of other worlds, out of the mistake of measuring them all with a Western yardstick. The real picture of our planet’s development is quite different…”

Solzhenitsyn’s Harvard speech culminated in a prescient caution: the Western model of living, increasingly, might not hold universal appeal, a sentiment underpinned by historical lessons for societies facing existential threats. He critiqued both the Communist and Western Capitalist paradigms that dominated the Cold War era, pinpointing the crisis in what he termed “despiritualized and irreligious humanistic consciousness.” According to Solzhenitsyn, the malaise afflicting modern societies originated from an overreliance on human judgment, flawed by pride, self-interest, and a litany of other vices. Humanity, he observed, had amassed significant experience since the Renaissance but had concurrently drifted away from the acknowledgment of a Supreme Entity, which once moderated our passions and irresponsibilities.

“To such consciousness, man is the touchstone in judging everything on earth — imperfect man, who is never free of pride, self-interest, envy, vanity, and dozens of other defects. We are now experiencing the consequences of mistakes that had not been noticed at the beginning of the journey. On the way from the Renaissance to our days, we have enriched our experience, but we have lost the concept of a Supreme Complete Entity which used to restrain our passions and our irresponsibility.”

Legacy and Reflection

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn remains a figure of towering moral and literary stature, a philosopher-publicist who dared to confront the darkest aspects of the 20th century. Through his works, he challenges us to examine the ethical underpinnings of society, urging a return to a sense of collective responsibility and spiritual renewal. As we reflect on his contributions a century after his birth, we find in Solzhenitsyn not just a chronicler of past horrors but a timeless voice calling for introspection and moral courage in the face of enduring human follies.

[…] psychology, and philosophy. Among its most recurrent references, we find names ranging from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn to Friedrich Nietzsche and Fyodor […]