There is an imperious mandate to abandon our intellectual possessions whenever we face the majesty of a world historical philosopher and follow the path the latter might enlighten for us, as Emerson accurately said (Emerson, 2001, p. 176). Hegel is one of such paragons that marks a route to many adventurers in the realms of philosophy until today. And he undoubtedly did so, in a more apostolic manner, during his lifetime. Yet the fugacity of his followers, of his own ´school´, which was to irrigate the fertile soil of modern philosophy, seems unsettlingly buried under the enormous weight of unruly heirs like Marx or Engels, who managed to subvert and erode the legacy of the last big representative of German idealist philosophy and transform it into a different kind of synthesis.

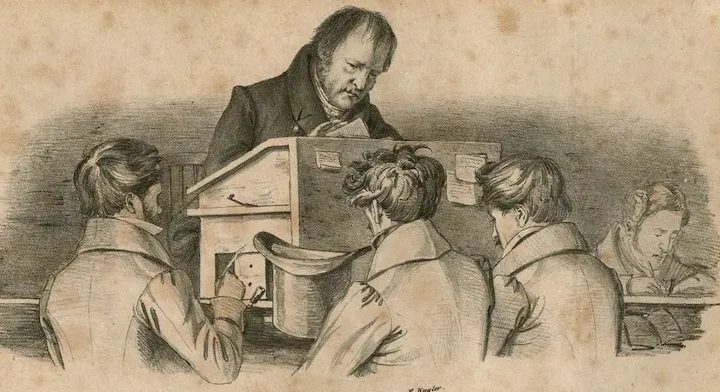

Whilst Marx and Hegel usually get most of the attention, the transitional stage between them, the spawning pool of revolutionary Hegelianism in the XIX century receives far less attention. When it happens, it’s the humanist Feuerbach or the theologian Strauss who mostly get clout. Not that their relevance is to be ignored, yet hidden pearls remain veiled to the contemporary reader. The most tragic of these lost Hegelians is Eduard Gans, the authentic heir to the chair of Law in the University of Berlin, the seat occupied by Hegel in life.

Gans not only bears the distinction of being the chosen heir to Hegel academic position, or Marx´s law professor in Berlin, he embodied the beginning of the worldly translation of Hegelian philosophy into a transformative and revolutionary philosophy, its concreteness into the turmoil and effervescence of post-revolutionary Europe. Revolutionary in regards of the Trois Gloriouses in 1830, that intermediate process of constitution of the modern nations in the continent and the rise to prominence of the bourgeoisie as the main political subject of the new era. The very same Revolutionary period that broke the determination of Hegel, the already aged professor, who had to confess his time had passed and he couldn’t understand this new epoch which saw such a blurry dawn.

Almost following the logic of the revolutionary cycles, Gans had the serious challenge of thinking the present world and the contradictions of the spirit of his time. Surrounded as he was by the contentious generation of the thirties in Prussia, and according to his own capacities as a professor, his main focus remained the relationship between the State and the civil society. Behind had remained the days when the very best of the German intellectual energy was drawn into the discussion of the transcendental deduction of categories. The historical present, in all his urgency, had diverted those who learned from the best, like Gans himself, into the open battlefield of the political reconciliation of the concept with reality. Germany was, notwithstanding, the spoils of the Napoleonic whims and merely an autocratic idea on the way of being materialized. After Walpurgis Night the modern German nation, which wasn’t still real, as a factum, but was on the way to becoming a reality, had undergone a fearsome transformation that took it down the path of nationalism. And its mere possibility of birth, even more after the wave of the 1830s, shook every bit of the social fabric of the disperse German domains. Gans, as a Jew, favored and defended by the enlightened Hegel, had to occupy his talents on the real rift that tore apart the Spirit of the nation where he belonged.

As a law professor his interests led him to the problems of poverty. While the rest of the young Hegelians, the Society of friends of the Eternal, devoted precious time to compile and ´organize´ the works of the ´Old Man´ who had passed away in 1831, the star proselyte continued the translation of Hegel into the practical philosophy which it should eventually become. Even before the ´official´ appearance of young Hegelianism with Strauss Life of Jesus, Gans was already occupied with the real problem that the Vormarz[1] Prussia had to face, the emergence of poverty, modern poverty in the form of the proletariat, dispossessed and unprotected by guilds (which had been dissolved) and states alike, within the dissolving dynamics of the initial rumblings of the beginning of German capitalism.

Completely aware of the social implications of the emergence of the Pobel[2], Gans shared the enthusiastic disposition to overcome the very existence of such a phenomenon, which he deemed an irrational state of affairs for a society (Bienenstock, 2011, p. 170). And his collusion with Saint-simonism, an adscription attributed usually to the German professor, that wasn’t enough to define him, since it was unacceptable for him to accept the reversal of secularization that this movement proposed as a mean to solve poverty. And it’s in this aspect of his thought that Gans represents the true spirit of the thirties Germany critical intellectual: a resolute opposition to the social malaises of the rising capitalism and a compromise to the Hegelian legacy in the form of respect to the conciliatory idea of the civil society, as a compensating factor to the state. The radicalism of Marx and Engels as well as the eccentricity of Stirner were the po sthumous sign of the aggravating state of the German society in the 40s, which had its outcome in the 48 revolution, but not yet during Gans lifetime.

If the topic of poverty, and the social question was to be less obvious in the more renowned early Hegelianism, as this was on the way to suffer the transformation of philosophy into a theoretical guideline of revolution, Gans had already made of it his main object of concern and work. As a teacher, rebellious within the limits of the German autocracy of the times, he kept his work as a crucial organizer of the Critic Journal of Philosophy, the counter academy which stood against the Royal Academy of Science that had denied access to Hegel (Pinkard, 2000). And despite the bastardized history that has made of Hegel and his immediate followers the ´defenders of Prussian State´, these, especially Gans, the Jewish Hegelian, were not so easily conformed with the current status of the German nation and the nationalist rhetoric that abounded in the legal and political theories that did reinforce autocracy, like Savigny´s, Gans bitter rival and main romantic theoretician of the State (Hoffheimer, 1995, p. 4) .

The socialization[3] and the tenuous relationships of the civil society with the state, the ultimate reality in the realm of politics were brought into questioning during every moment after the initial stages of the liberal uprisings in Europe. Socialization, for Gans, as a German interpreter of the French idea of association, was not a mere labor union, which should protect the workers from the factory owners. This specific post Hegelian (since Hegel thought the State to be the tutor of the civil society) way to see the problem, which envisaged the State with a necessary presence, considered the empowerment of the civil society, as an organized body of producers and workers in an edifying conflict with the state. Nonetheless, his awareness of the core problem of proletarianization was very clear (Gans, 1836, p. 100).

Despite his differences with Saint-simonism, his fascination with the French revolution and the urgency of the social problems which he prioritized made him a real advocate of a more practical Hegelianism, hence a supporter of the worker’s right which this movement defended. However, Gans´s rejection of the religious fight against concurrence by Saint-simonians entailed the assumption that individual rights couldn’t be dismissed, and the idealistic state they proposed only drowned the achievement of modernity, the subjective freedom (Breckman, 2001, p. 549).

Why would the relentless pace of the history of philosophy condemn Gans almost to invisibility? Undoubtedly, his early demise meant a break in his rise to prominence within the progressive post Hegelians. As remarkable as he was for his opposition to the historical school, as Bentham himself acknowledged (Gans, 1836, p. 201), he couldn’t survive the thirties and become the beacon of a socially and politically compromised generation which included Marx, who was his pupil for two courses at Berlin University. Whether his relationship with Marx was crucial or not, his role in the radicalization of Hegels thought, and one might add, Hegelianism as such, is underscored, but it’s still worthy of featuring more prominently in the golden pages of the Young Hegelians.

Notes

[1] Germany between the revolution of 1830 and the revolution of 1848.

[2] Populace.

[3] A concept akin to associationism.

References

Bienenstock, M. (2011). Between Hegel and Marx. Eduard Gans on the ‘Social question’. In Politics, religion and art: hegelian debates. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Breckman, W. (2001). Eduard Gans and the crisis of Hegelianism. Journal of the History of Ideas, 62(3), 543-564.

Emerson, R. W. (2001). Essays. In J. Manis (Ed.).

Gans, E. (1836). Rückblicke auf Personen und Zustände. Berlin: Verlag von Veit und Comp.

Hoffheimer, M. H. (1995). Eduard Gans and the Hegelian philosophy of Law. Dordrecht: Springer.

Pinkard, T. (2000). Hegel. A biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.