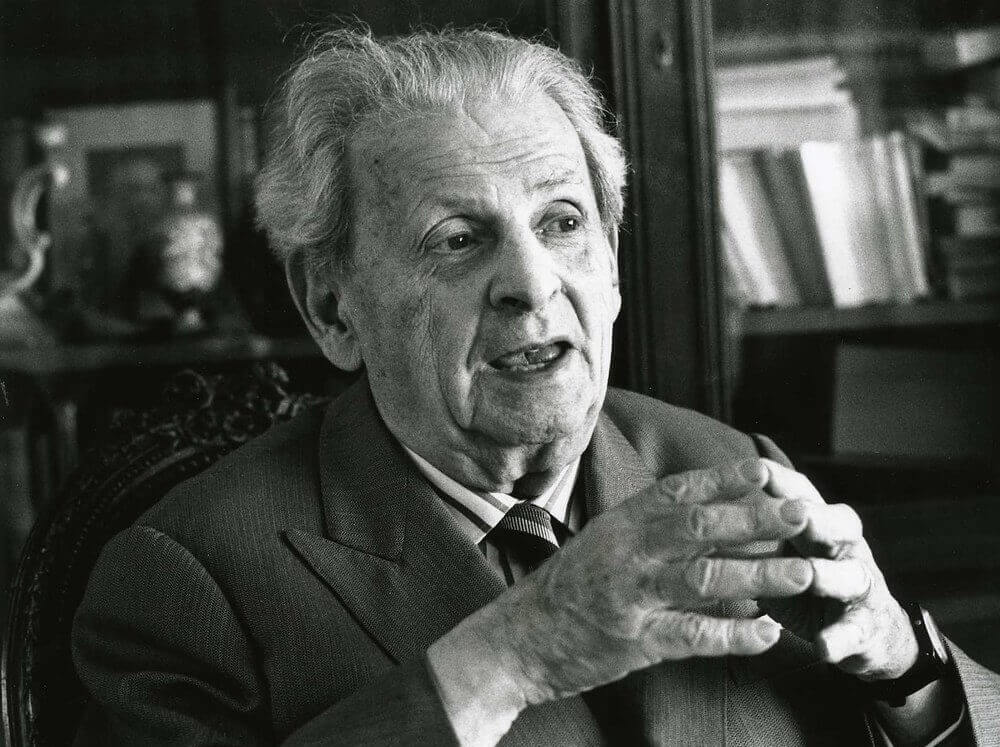

Introducing Emmanuel Levinas

The philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas is the result of the influence of the group of the three H (G. W. Hegel, Edmund Husserl, and Martin Heidegger). Originally from Lithuania, he is one of the most famous representatives of continental philosophy. To understand his work is also to enter suddenly into the fundamental debates of our time.

In recent years, the debate about its relevance has been revived, more specifically about his role within the phenomenological movement. However, its importance goes beyond the theoretical scope. Among the most discussed ideas, we recall his criticism of Western metaphysics, which has forgotten ethics as the central theme of philosophy. We also find the definition of a new human subject in his “face-to-face” relationship with the other.

Its key concept, then, is contained in the French word autrui, which designates the other. We have to see in this one a figure of another human being and not a thing that can be scientifically known. Then, his proposal underlies an ethical reflection of said figure. That is, it helps us overcome the individuality that accompanies absolute freedom and to understand how that “face” in front of us acquires relevance.

For the Lithuanian philosopher, the task is to conceptualize this idea as embodying “the orphan, the widow, and the foreigner.” That is, to contemplate the individual who has severed or lost their connection to the encompassing whole. It is upon this foundation that we can reconstruct our bond with the world, including all things within it.

His life, the history of the European Jew

His life mirrors the narrative of the European Jew, with numerous aspects today still shedding light on the Jewish influence in his philosophy. A clear illustration of this is seen in the publication of two of his works, Quatre lectures talmudiques (1968) and Difficult Freedom: Essays on Judaism (1963).

Exploring his life further, we start with his arrival in Strasbourg, which is marked by his friendship with Maurice Blanchot. We then follow him to Freiburg, where he delves into phenomenology. Just as he starts to adapt to the new epochal spirit, he lays the groundwork for his critique, leading to the 1930 publication of his thesis, The Theory of Intuition in Husserl’s Phenomenology.

Years later, Levinas enlisted in the French army, only to be captured in 1940 and spend the next five years as a prisoner of war.

Upon his release, he returned to his homeland to find that the Nazis had murdered his entire family. Miraculously, his wife survived, thanks to the protection of nuns who hid her from harm.

Levinas then took up a position as a professor and administrator at a Jewish educational institute in Paris. It was there that he began his deep dive into traditional Jewish texts, mentored by the esteemed Mordechai Shoshani.

In 1961, Levinas presented his first major work, Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority, at the Sorbonne’s philosophy faculty. He later joined the faculty as a philosophy professor.

His second seminal work, Otherwise than Being or Beyond Essence, was published later, marking another significant contribution to philosophical thought.

Levinas passed away on December 25, 1995.

Abraham’s discourse in Western philosophy

Levinas is first known for his direct attacks on the thought of the German philosopher Martin Heidegger. Fundamentally, by the indifference of the latter towards the ethical issue and its “totalization of the other.” In this aspect, one should not ignore Heidegger’s approach to the Nazi party.

Like several in those years, Levinas also confronted Hegel. This one and its phenomenology were the horizons of the meaning of an entire generation that took on the task of reinventing the relationship between the totalizing dialectics and the particular moments of being.

Jacques Derrida, in his essay Violence and Metaphysics, has already given us the key to understanding the importance of Levinas. Unlike Hegel, the author of Totality and Infinity proposes a journey that moves away from the totality as a sign of identity. Thus, the new route of Western philosophy and culture is that of Abraham and not of Odysseus, not identity but difference.

Let us recall what Simon Critchley stated about that:

“Philosophy as ontology is always a return to the same, always Ulysses returning to Ithaca after ten years of wandering around the Mediterranean getting into all sorts of trouble, eventually) returning home to find out whether or not his wife has been faithful. We oppose that to the story of Abraham, who leaves his country forever and goes into the desert, the story of exile and wandering. That is the Levinasian narrative.” (1)

The death of the Other and the responsibility

His conception of responsibility is also radically different. Instead of seeing that concept as another way of inserting the other into our world, the philosopher raises a much more open relationship in which the I is questioned by the presence of the other.

Therefore, responsibility is not only to take care of others but also a self-questioning of our identity. It is in this aspect where we will also find his reflection on death: “The other individuates me in the responsibility I have for him. The death of the other who dies affects me in my very identity as a responsible ‘me’.”(2)

Although in other thinkers, the reflection on death leads to ethical proposals, it is not until Levinas that we can find a more systematic effort. An ethic in the strict sense of the term that derives from the death of the other. The other is not an enemy that steals my life after I die but a sign of a responsibility that touches me at all times.

In the field of criticism against Levinas, we find the ones referring to the language he uses. However, it is also pointed out his lack of conventionalism in ethical and ontological aspects. Undoubtedly, his work is complex and takes time to mature. However, once inside, we recognize that Levinas speaks to us from the “outside” of theoretical knowledge. Also, this does not happen because of any adventurism. I think it is instead a serious invitation to think, first, about the ethical basis in our relationship with others, then to address the systematic totality of science and other knowledge.

In times when a particular type of rationality constantly calculates costs and benefits, or perhaps the probable ways in which we die, Levinas becomes more necessary.

[…] Emmanuel Levinas (1906–1995) tried to define a relationship with the other differently. He was born in Lithuania, and he is one of the most celebrated representatives of the continental philosophy. […]