A bridge to the French philosophy of the 20th century

The spiritualist vitalism of the French thinker, sprinkled by a vigorous mysticism, stands out among the numerous reactions at the beginning of the 20th century due to the preponderance of positivism and mechanistic materialism in the western scenario.

His thoughts tackle two fundamental problems. First, the notion of intuition, specifically the intuition of duration. Second, the criticism of the naturalistic reduction of man that prevails in the positivist interpretations of evolutionism.

In defense of the despised spiritual dimension of man, his thought becomes a point of convergence of the French spiritualism of Main de Biran and Ravisso, not to mention the Anglo-Saxon evolutionism of Herbert Spencer.

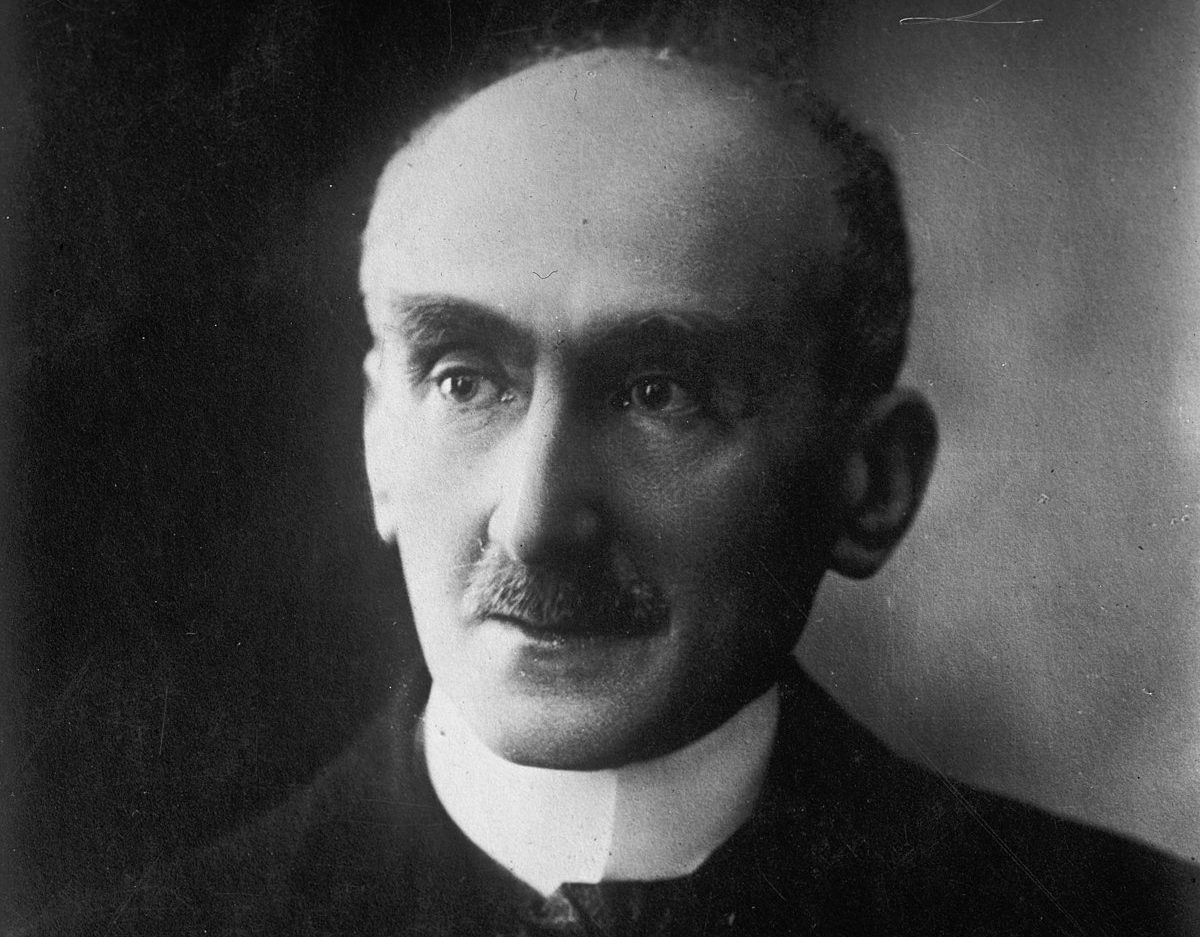

Henri Louis Bergson was born in Auteuil, France, in 1859. He was the son of an Irish woman and a Polish of Jewish origin. He studied philosophy at the Ecole Normale Supérieur and from a very young age became involved in teaching at numerous French high schools. During these years, Bergson becomes familiar with the works of many of the determining authors in the elaboration of his theories. In 1889 he obtained his doctorate with two theses: Quid Aristotle de loco senserit and, Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness (Essai sur les données immédiates de la conscience). Besides, in this context, he publishes some of his most impressive works: Matter and Memory (Matière et mémoire, 1896), Laughter, an essay on the meaning of the comic (Le Rire. Essai sur la signification du comique, 1900) and Creative Evolution (L’Évolution créatrice, 1907).

The reputation that earned his work gave him the opportunity to obtain a chair at the famous Collège de France. During the First World War, Bergson occupies various diplomatic positions on behalf of the French Republic. This fact will provide an excellent opportunity for the dissemination of his theories. Thus, he even lectures at distinguished American universities.

In 1914, he became part of the French Academy. Moreover, later he was recognized with the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1928. He died in 1941 during the occupation of France by Nazi Germany. Other notable works are Duration and Simultaneity (Durée et Simultanéité, 1922), and The Two Sources of Morality and Religion (Les Deux Sources de la morale et de la religion, 1932).

Henri Bergson: A Brief Introduction to his Philosophy

Bergson intends to overcome the rational and teleological character of the evolutionary theory. He will try to do this by examining the notion of process in which the vital energy is wasted without any purpose.

From here, he derives his affirmation that man as he exists today —like all living organisms— is only the result of one of the infinite possibilities in which the evolutionary process could have ended. Therefore he is not a logical outcome previously planned by Nature. Man is neither rational nor acts governed by patterns.

This irrational behavior, says the author, will be marked by impartiality, by which the vital élan —a metaphysical principle that somehow recalls “the will” of Schopenhauer or “the will to power” of Nietzsche— is manifested without privileges. The attempt to reinterpret scientific data leads to a recurring theme in Bergson’s work: the problem of the status that philosophy should occupy in a world in which scientific discourse reigns as a legitimating value. Bergson writes Introduction to Metaphysics (Introduction à la Métaphysique, 1903), to demonstrate that philosophy could have similar objectivity to that of the positivist sciences. However, its metaphysical foundation has a slightly different nature because it accepts the variability and the multiple.

Intuition and duration

The Introduction to Metaphysics begins with the distinction between two sources of knowledge: intelligence and intuition. He starts defining the inability of the first one —highly valued in Western culture, to the detriment of the second one— to explain vital phenomena.

According to Bergson, the dynamic nature of reality makes it impossible for the intellect, determined to establish mental tables and to depend on representations, to grasp it in its essence. “There is an external reality and, nevertheless, given immediately to our spirit. […] That reality is mobility.” The way in which reality is immediately given to us, he emphasizes, it is through intuition.

The Bergsonian intuition, the evolutionary result of the instincts, proceeds in the sense of life and expresses itself as the overcoming of the discursive reason. Understood as immediate consciousness, Bergson turns it into a method that sets out to determine the conditions by which we can consider the integrity of problems.

With this, he seeks to overcome the dependence of the symbol to which both, the sciences and metaphysics, are concerned. These affirmations lead to a rupture that occurs in this new way of grounding metaphysics in intuition and, by extension, as the means by which philosophy develops, since the spiritual dimension and vital phenomena escape the domain of the typically distancing rational discourse.

From the formulation of intuition, he turns on to the complex notion of duration (irrational time that seeks to overcome abstraction and insensitivity to the qualitative differences of mathematical time). In the same way, intuition opens the way to the differentiation of natures between past and present, produced at the base of a conception of memory that, in clear opposition to the way in which psychology and a large part of the philosophical tradition has conceived it, establishes an inverse movement from the memory to the perception. All these topics were very discussed in the academy. The very notion of duration, especially the intuition of duration, becomes highly controversial.

Conclusion

With Bergson, the tense position generated by the metaphysical theme for the twenty-first century seems to relax, not being utterly alien. Giving science the metaphysical dimension that it lacks and not supplanting one for the other one, that is the crucial intention of the philosophy of the French thinker.

Understanding Bergson’s legacy today makes us look Science with different intentions. Without being a Martin Heidegger, Sartre or Merleau-Ponty, at least it offers us an alternative. It is true; perhaps it is not an idea as complex and consistent as intentionality. However, at least it invites us to think about the continuous relationship of man with the world. Also, the complex nature of our intuition. All this in times in which neither intuition, nor world, nor spirit, are thought in depth.

As Gilles Deleuze pointed out: “To continue with Bergson today is, for example, to constitute a metaphysical image of thought that corresponds with the new planes, relationships, jumps, dynamisms discovered by molecular biology of the brain: new chaining and re-chaining in thought.”

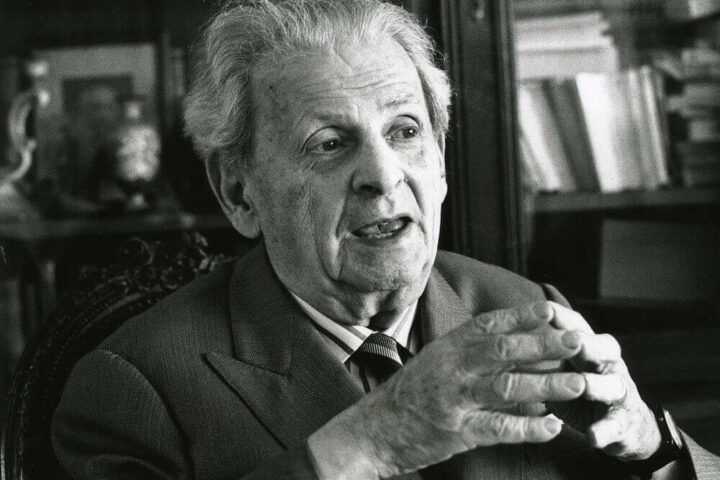

[…] 1911, Emil Michel Cioran studied philosophy at the University of Bucharest. His final thesis was on H. Bergson. In 1937, he received a scholarship from the French Institute and went to Paris where he lived most […]