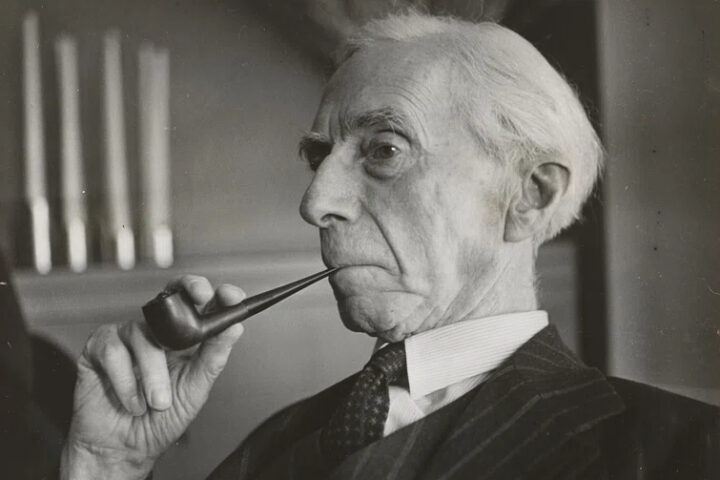

The philosophy of Karl Marx has made a lasting mark on universal history with his profound critique of 19th-century capitalist society and ideology. Drawing deeply from German classical philosophy, Marx crafted an innovative social analysis that also critically engaged with ideas from English political economy and French socialism. Yet, the critical essence of his work has transformed him into a spectral figure, one that invariably resurfaces during periods of tension and crisis in modern history.

Born in Trier, Germany, in 1818, he was the son of a middle-class Jewish family. He studied law in Bonn and Berlin and then finished his doctorate in philosophy, entitled “The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature.”

This essay was considered a controversial work, especially among professors at the University of Berlin. Precisely for this reason, Marx decided to present his thesis to the University of Jena, whose faculty awarded him the doctoral degree in April 1841. The research was described as “a daring and original piece of work in which Marx set out to show that theology must yield to the superior wisdom of philosophy” (1)

Due to the radical nature of his views, he was unable to secure an academic position, which led him to pursue journalism. During this period, he contributed to the Rheinische Zeitung (Rhineland News), where he started to apply Hegel’s philosophy, particularly the dialectical method. In 1843, he relocated to Paris and began working with other radical publications, including the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher (German-French Annals) and Vorwärts! (Forward!).

Of his many early writings, Introduction to a Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right and On the Jewish Question stand out, both of which were written in 1843 and published in the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher. In the first of these texts and precisely on criticism, he tells us:

“It is, therefore, the task of History, once the other-world of truth has vanished, to establish the truth of this world. It is the immediate task of philosophy, which is in the service of History, to unmask self-estrangement in its unholy forms once the holy form of human self-estrangement has been unmasked. Thus, the criticism of Heaven turns into the criticism of Earth, the criticism of religion into the criticism of law, and the criticism of theology into the criticism of politics.” (2)

Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, written in Paris, and the Theses on Feuerbach of 1845, although unpublished during his life, have also been two of the documents that have aroused interest in recent debates, inside and outside the academy.

Despite being incomplete, the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts provide a groundbreaking interpretation of alienation in relation to labor, the outcomes of labor, others, the worker’s environment, and the material essence of humanity itself.

This concept highlights that the fruits of labor are estranged from the laborer, indicating a fundamental bond between a person and their work that remains unfulfilled. Given that both material and intellectual production form the cornerstone of human endeavor, alienation extends across the entire system encompassing human existence:

“An immediate consequence of the fact that man is estranged from the product of his labor, from his life activity, from his species-being, is the estrangement of man from man. When a man confronts himself, he confronts the other man. What applies to a man’s relation to his work, to the product of his labor and to himself, also holds of a man’s relation to the other man, and to the other man’s labor and object of labor.” (3)

Thus, far from reducing his criticism to an operation or device against divine power and ideology, it should be seen in terms of a more general movement that does not concern only people or specific spheres of social life.

This dynamic is vividly captured in the progression evident in his work, which, from a logical perspective, incorporates numerous Hegelian elements that we lack the time to detail at this moment. In essence, criticism extends beyond merely revealing the foundational conditions of our reality or launching a straightforward critique against the other (be it the object, the world, or values). It also involves highlighting the isolation, restriction, exploitation, and alienation experienced by individuals. These individuals face off against one another, yet fail to recognize the encompassing nature of their actions.

Other significant contributions include The German Ideology, co-authored with Engels in 1845, and The Communist Manifesto, arguably Marx’s most famous and widely read work, possibly due to its less theoretical nature. For a proper understanding, it should be contextualized within the broader corpus of Marxist theory rather than viewed in isolation, as some contemporary thinkers have attempted. A case in point is the superficial analysis by Jordan Peterson, who posits the existence of a so-called Marxist postmodernism without offering a thorough explanation or solid basis for his claims.

In works like the Communist Manifesto and The German Ideology, the critique expands into the domain of history. In The German Ideology, Marx and Engels set their materialist approach against the idealism that dominated prior German philosophy. They aim to lay the groundwork for the materialist method, challenging the purported radicalism and critique inherent in that tradition. They point out a significant oversight. In fact: “It has not occurred to anyone of these philosophers to inquire into the connection of German philosophy with German reality, the relation of their criticism to their own material surroundings.” (4)

Moreover:

“In direct contrast to German philosophy which descends from heaven to earth, here we ascend from earth to heaven. That is to say, we do not set out from what men say, imagine, conceive, nor from men as narrated, thought of, imagined, conceived, in order to arrive at men in the flesh. We set out from real, active men, and on the basis of their real life-process we demonstrate the development of the ideological reflexes and echoes of this life-process. The phantoms formed in the human brain are also, necessarily, sublimates of their material life-process, which is empirically verifiable and bound to material premises. Morality, religion, metaphysics, all the rest of ideology and their corresponding forms of consciousness, thus no longer retain the semblance of independence. They have no history, no development; but men, developing their material production and their material intercourse, alter, along with this their real existence, their thinking and the products of their thinking. Life is not determined by consciousness, but consciousness by life. In the first method of approach the starting-point is consciousness taken as the living individual; in the second method, which conforms to real life, it is the real living individuals themselves, and consciousness is considered solely as their consciousness.” (5)

Following the 1848 revolution’s collapse, Marx relocated to London, where he spent the remainder of his life focused on studying political economy. It was there that he finalized A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy in 1859.

In 1867, after a stay at the home of his friend Kugelmann in Hannover in which he corrected the first galleys, he published the first volume of Das Kapital (English title: Capital: Critique of Political Economy). This work addresses the capitalist production process in its entirety. In this work, Marx develops his theory of value and his notions of surplus value and exploitation, grounded in the enigmatic nature of commodities. This critique serves as a gateway to understanding the complex web of social relations that underpin the violence and desperation with which people struggle for basic necessities. “A commodity appears, at first sight, a very trivial thing, and easily understood. Its analysis shows that it is, in reality, a very queer thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties” (6).

It is through the detailed analysis of the commodity system that the structure of society is laid bare. Yet, the question remains on how to make this process comprehensible to individuals, or in other words: How can the alienated individual be liberated from this web of exploitative social relationships? With the roots of human crisis clearly revealed, why does one not act to save oneself but instead delve deeper into one’s metaphorical cave?

Volumes II (1885) and III (1894) of Capital were kept as manuscripts in which Marx continued to work for the rest of his life; they were published posthumously by Engels.

Clearly, the texts mentioned are but a small fraction of Marx’s extensive oeuvre, which is expected to encompass around 100 substantial volumes upon the completion of his collected works. Nonetheless, they serve to underscore a crucial aspect we wish to emphasize: the inherently critical nature of his approach.

Karl Marx and (philosophical) criticism

Marx forges his thought in the combination of history, philosophy, and political economy. This position led him to conceive and raise the need for a theoretical-practical appropriation of reality. Its militancy and its proximity to the conditions of the working class resulted in a set of concepts and theories that, guided by practical activity, led to the social revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat as a final alternative to social contradictions.

In a survey carried out by the BBC in 1999, he was considered by readers as the most influential thinker of the millennium. In this list, he was mentioned along side with Albert Einstein, Isaac Newton, Darwin, Saint Thomas Aquinas, Hawking, Kant, among others.

Detractors there have also been many. An example is Karl Popper, who blames Marx for his theoretical participation in the construction of social science that tries, from essentialism, to lead History towards an immovable set of universal laws.

Others, for their part, identify him as a significant influence and father of modern Social Sciences.

Irrespective of how his work is interpreted, the critical element stands as a pivotal counter to the notion of Marx perceiving history merely as a set of immutable laws. Moreover, Marx’s work challenges the dogmatism of intellectual bureaucrats who treat his writings as a mandatory scripture. The implication is clear: were Marx alive today, he himself would not be a Marxist.

If there’s anything Marx, the philosopher, can offer us today, it is, firstly, a new way of understanding truth that enhances our discernment, and secondly, the practical moral guidance we desperately need. Criticism, in this context, is not about achieving clarity or uncovering a truth tied to a specific object. Rather, it is a multifaceted concept aimed at unveiling reality as a system and network of social relationships. It’s not about the truth of one situation or another, or the univocal understanding, but about truth as a practice that exposes ideology.

Notes

- Wheen, Francis (2001). Karl Marx. London: Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-1-85702-637-5.

- Marx, K. (1970). Introduction to A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/Marx_Critique_of_Hegels_Philosophy_of_Right.pdf

- Marx, K. (1959), Estranged Labour. In Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844. Moscow: Progress Publishers. Retrieved from: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/manuscripts/preface.htm

- Marx, K. & Engels, F. (1968). The German Ideology. Moscow: Progress Publishers. Retrieved from: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/german-ideology/ch01.htm

- Idem

- Marx, C. (1999). Capital (Vol. I). Moscow: Progress Publishers. Retrieved from: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/index.htm

cheap iptv jamaica

Say, you got a nice blog.Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.