“The whole life of those societies in which modern conditions of production prevail presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. All that once was directly lived has become mere representation.”

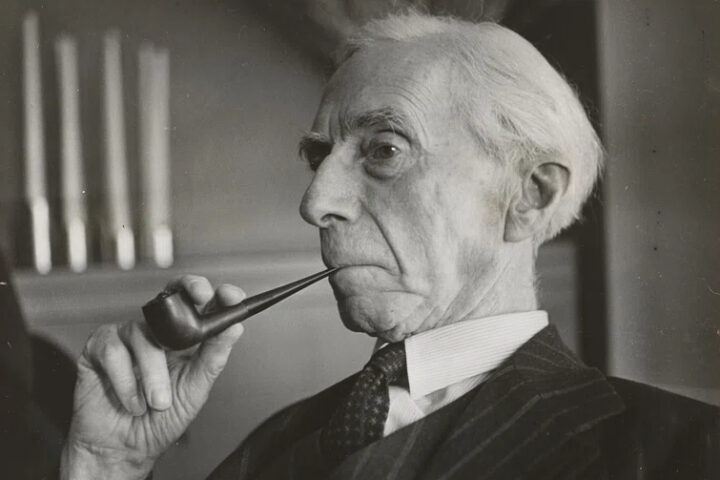

Guy Debord

Previously, we have spoken about the reigning affectivity of our century, characterized by an “empathy wrapped in 08-bit cellophane”, a superfluous way we have chosen to love and be loved by employing a virtual reality in which everyone participates to be seen, but rarely to interact with meaning. But today, we are interested in exploring a fundamental aspect: the immeasurable value that privacy and anonymity have in our days in the face of the culture of permanent and unbearable constant exposure.

In his work La société du spectacle (1967), the writer, filmmaker, and philosopher Guy Debord (1931-1994) clearly exposes a model of life that has been dominant in Western societies since the beginning of the twentieth century. Basically, our thinker wanted to express that we live in an existential theater in the form of a screen in which the sense of existing depends directly on the exposure and the “need” to be seen all the time.

The ontological translation of what we have just expressed would be “if I am not seen, I do not exist.” In this type of existential discourse, it does not matter what one thinks or does, but what is projected in a representation that must be worthy of being seen and enjoyed.

It may seem to us that Debord’s statement is exaggerated, but, dear readers, if you take a few moments, temporarily suspend the reading of this text, take your cell phone, open any social network and start sliding your index finger upwards in the “news” section: you will find personal and intimate information of more than 300 people who have voluntarily decided to show absolutely all the nooks and crannies of their privacy for free.

The excuse for using these devices is to “get in touch” or “meet” people, but I ask you, do you really know a person through a social network? What I do not doubt about is that you will know where they went on vacation, what cultural event they attend, where and what they eat, how they dress and where they buy what they wear, who they socialize with and who they admire, but who they are, I seriously doubt it.

Perhaps you have heard of the panopticon. A panopticon is a type of prison structure devised by the English jurist and philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832). Its purpose was to achieve total control of surveillance in a given area by installing a tower in the center of it. This tower would allow guards complete and clear visibility over each inmate’s cells.

The idea revolutionized the architecture not only of prisons but also of most public buildings (courthouses, schools, doctors’ offices, or hospitals). It was even incorporated into the design of people’s own homes. The specific utility of the panopticon was centered on the ability to see without being seen and to watch those who do not know they are being watched. Although we all know that there are observation posts, we never see the face of the observer.

The specific utility of the panopticon was centered on the ability to see without being seen, to watch those who do not know they are being watched, since, although we all know that there are observation posts, we never see the face of the observer

Being seen without seeing the one who sees us produces a feeling of permanent vigilance and alertness in the face of such ignorance, which has the function of causing a corresponding fear to avoid any kind of improper behavior. Now, what interests us today through this brief reflection is that we can see how we have gone from living among surveillance devices to being ourselves, the providers of information and self-surveillance at the service of megacorporations that sell the device to entertain us, but that in the end is a machine to produce information and data through the voluntary exposure of our “profiles.”

Beyond the pure narcissism of constantly posting photos of our intimate life on social networks, it is interesting to evaluate what we lose in the unhealthy dynamic that represents the life of the living mannequin. What is protected and not shown is valuable, worthy of respect, and even sacred. At the same time, what is freely exposed is always gossip and a source of massive trivialization of a horde of disinterested people with the power of opinion. To think that my life is meaningless because total strangers do not see it is the same as thinking that if I close my eyes, I cease to exist. If we attend a game of any sport, it is supposed to be to watch the spectacle, alone or not. Still, the cultural experience only makes sense if I watch it through a camera that shares what I see with all my contacts. I ask you honestly, does it make any sense whatsoever to let a thousand strangers know my geographical location and the full view of what I am performing? Is the experience real when it is so sifted by the pictorial representation that we create ourselves for others to see what I am seeing?

What is protected and not shown is valuable, worthy of respect, and even sacred. At the same time, what is freely exposed is always gossip and a source of massive trivialization of a horde of disinterested people with the power of opinion. To think that my life is meaningless because total strangers do not see it is the same as thinking that if I close my eyes, I cease to exist.

Finally, it seems we cannot overcome the cave Plato used to explain so many fundamental aspects of life, knowledge, and the meaning of existence.

Living from the shadow we produce for others is the same as being slaves of our own shadow, permanently created with filters and stickers whose only purpose is not to say “this is me” but rather “this is what I want you to believe is me.”

Returning to the fictitious motivation of social networks: is that meeting people? Hundreds of thousands of people will be surprised every day when they corroborate that the human being in front of them at the table has nothing to do with the character displayed on the mobile screen. Real people have little to do with the fiction represented in the feed and the stories on social networks.

To corroborate this, it is enough for me to attend the exit of a school waiting for my daughter to finish her school schedule: no less than 80 fathers and mothers, one standing next to the other, all with their necks bent towards a screen and no one talking with anyone, no one knowing anyone; no one knowing who anyone is. The alienation that occurs is such that we prefer to see a person’s digital profile rather than having to chat personally with them tediously. The level of abstraction and individualism that represents the abandonment of real and concrete social life has precisely led us to trivialize our existence and that of others in a way that causes fright and fear: if something happens to you and you post it, you will receive reactions and comments; if something happens to you in the street and you need help, you will receive silence: in short, we are becoming atomized antisocial citizens subjugated by prisons with panopticons that we installed in our lives.

The philosophical problem presented here has to do with the preservation of our being and our affections through the protection of anonymity in the face of the constant media demands that insistently coerce us to be “notorious” and noticed to believe that we truly exist.

The level of abstraction and individualism that represents the abandonment of real and concrete social life has precisely led us to trivialize our existence and that of others in a way that causes fright and fear.

The ethical consequences of this pathetic type of existence represent a personal and voluntary surrender of strictly intimate aspects before “a legion of imbeciles who used to only talk in the bar without harming anyone” (Umberto Eco).

We have seen how people’s lives and reputations have been ruined through leaks of audiovisual material that portrays aspects that should not be massively disclosed. And no matter how much the progressive and nihilistic postmodern culture tells us that such exposure is the result of an idea of freedom, we corroborate that this is a lie when the victim of disclosure of private information suffers and cries out for the content to be taken down from the web or asks heartbreakingly to please stop sharing that photo or video.

The challenge to which critical philosophy invites us is to abandon the voluntary servility of permanent alienation

In the end, and as we always maintain, the challenge to which critical philosophy (not servile and justifying atrocities) invites us is to abandon the voluntary servility of permanent alienation that, while it entertains us, exposes and delivers us in the most intimate part of our being, ontologically equating us to the thing worthy of being seen and consumed instead of presenting us as human worthy of being truly loved and known for what we really are.