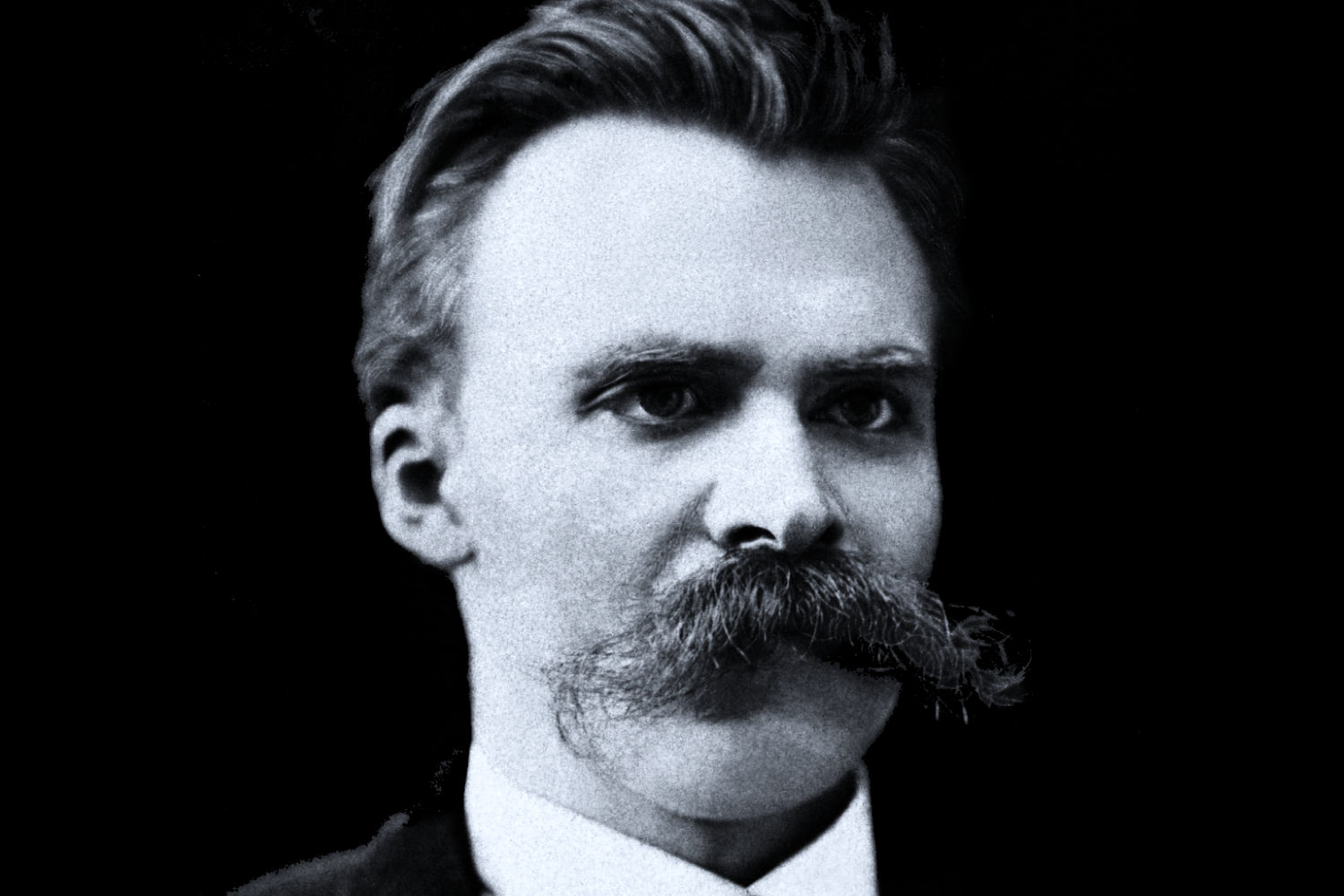

The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche

Phenomenologists, existentialists, poststructuralists, and postmodern thinkers have all acknowledged their intellectual debt to Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophy. This is due not only to the sharpness of his critique and his radical break with convention but also to the deeply autobiographical nature of his work and the contentious history of its misinterpretation.

Initially famous in early 20th-century Germany, Nietzsche’s philosophy was later condemned after being co-opted by the Nazi regime. It was only in the late 1950s that his ideas were rehabilitated by Italian and French revolutionary thinkers.

His thought emerges within the broader crisis of the ideals of progress and Enlightenment rationality. It coincides with the collapse of classical philosophical systems, the decline of Christian religious authority, and the rise of scientism.

Through aphorisms, allegories, and references to religious and philosophical traditions, Nietzsche moves from an initial philological focus on classical antiquity to a genealogical critique that seeks to expose the roots of Western thought and its consequences in the 19th century.

To live is to suffer; to survive is to find some meaning in the suffering.

— Friedrich Nietzsche

The Life of Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was born on October 15, 1844, in Röcken, Prussia. The son of a Protestant pastor, he was orphaned at a young age and raised by his mother and sister. This early experience shaped his lifelong engagement with religious controversy and influenced his complex views on women.

He studied Classical Philology at the Universities of Bonn and Leipzig. His exceptional intellect earned him a position as Professor of Classical Philology at the University of Basel, where he conducted most of his academic work. The University of Leipzig later awarded him a doctorate in recognition of his publications.

However, deteriorating health forced Nietzsche to abandon academia and embark on an extended journey through southern Europe, a period in which he produced most of his major works. As his condition worsened, he spent his final decade in nursing homes, mentally incapacitated.

Ironically, it was during this period that his work, once met with hostility in academic circles and largely unknown to the general public, began to gain widespread recognition. Nietzsche only became aware of the increasing interest in his philosophy toward the end of the 1880s, when his ideas were studied at the University of Copenhagen.

He died on August 25, 1900, in Weimar.

“The snake which cannot cast its skin must die. As well the minds which are prevented from changing their opinions; they cease to be mind.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche

Major Works

Nietzsche’s writings are now regarded as philosophical classics. His extensive body of work has been classified in various ways, reflecting the evolution of his thought. His intellectual journey spans:

- A metaphysical phase, influenced by Schopenhauer and Wagner.

- A critical engagement with Enlightenment scientific ideals.

- The mature phase, marked by the development of his own concepts, expressed through neologisms that, while retaining earlier influences, articulate a unique and radical vision.

Some of his most influential works include:

- The Birth of Tragedy (1872)

- Human, All Too Human (1878)

- The Gay Science (1882)

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883–1892)

- On the Genealogy of Morals (1887)

- Ecce Homo: How One Becomes What One Is (published posthumously in 1908)

Philosophy as a Way of Life

In Nietzsche’s thought, philosophy is not merely an intellectual pursuit but a way of life. He argues that existence itself is constructed through philosophy, which must recognize the tension between life and logos.

One of his most striking and enigmatic projects is the overcoming of nihilism, embodied in his concept of the Übermensch (the Superman).

The Overcoming of Nihilism and the Superman

Nietzsche saw the late 19th century as a period in which modernity had asserted its revolutionary ideals, yet humanity had failed to evolve. Man remained dependent, still seeking external justifications for his existence. Instead of freeing himself, he had merely exchanged theological dogma for scientific determinism.

He called this stagnation the Last Man—a complacent, fearful figure who clings to comfort and security while avoiding the burdens of responsibility and self-overcoming. The Last Man seeks meaning in absolute truths, elevating himself through external validation rather than internal transformation.

In contrast, Nietzsche’s Superman represents the triumph over nihilism. This figure embraces life in its entirety, recognizing suffering and chaos not as obstacles but as essential aspects of existence. He rejects repression, affirms his fate, and lives with a Dionysian spirit—creative, joyful, and uninhibited by external moralities. Most importantly, he is the one who embraces the eternal return.

“What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not a goal.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche

The Eternal Return

Far from being a mere metaphysical doctrine, the concept of the eternal return has profound ethical implications. It is not about a literal repetition of events but about the affirmation of life in its totality. Nietzsche challenges us to live in such a way that we would be willing to repeat our existence eternally, without regret or need for external justification.

This radical acceptance of responsibility led philosopher Max Scheler to describe Nietzsche’s atheism as the atheism of seriousness and responsibility.

At the heart of Nietzsche’s vision is the rejection of any external justification—be it God, metaphysics, or science—that serves as an escape from personal responsibility. Instead, he calls for an existence that fully embraces freedom, creativity, and self-overcoming.

[…] Among its most recurrent references, we find names ranging from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn to Friedrich Nietzsche and Fyodor […]

[…] Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), in On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense, tells us that our distinctive feature is to have invented truth (which he interprets as ” a useful error”). But the Stoics pointed out that what makes us what we are is our “social being” that has the capacity to reason. […]