Michael Lazarus, Monash University

Ruben Östlund’s 2022 film Triangle of Sadness has attracted both praise and criticism as a satire of the world’s rich. Triangle of Sadness follows the familiar plot of a castaway story. A luxury cruise ship capsizes after a disastrous drinking session between the captain (an American communist) and a passenger (a Russian capitalist) in the midst of a storm, leaves the ship vulnerable to pirates, who blow it up. Several passengers escape and fight to survive on a desert island.

However, their social rank, class and privilege are washed away with the shipwreck. To survive, they cannot rely on their prevailing social power: money. Instead, each person must act in self-interest. This situation provokes depravity from the survivors and it is this aspect of the film that brings the success of its satire into question.

Satires employ allegories and moral fables to expose social dynamics and, often, make a political critique. But the easy corruption and ruthless, self-interested competition of each character in Triangle of Sadness seem to confirm rather than confront the dominant ideologies of global capitalism: get ahead or die.

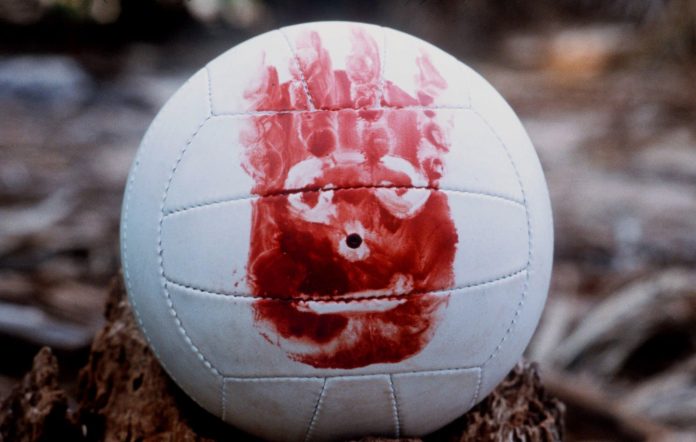

The trope of shipwrecked survival is probably most paradigmatic in Robert Zemeckis’ prize-winning blockbuster Cast Away (2000), starring Tom Hanks. Surprisingly self-serious, the film presents the audience with a ready-made morality tale.

By no fault of his own, a lone individual gets stranded on a desert island. Forced to survive from the ground up in adverse conditions, Chuck Noland (Hanks), demonstrates the power of the individual to persevere, proving his strength, ingenuity and determination. The only company Chuck has on the island is a volleyball he personifies, naming it after the sports brand adorning its surface – Wilson.

More recently, Ridley Scott’s The Martian (2015), had Matt Damon farming Mars, claiming “once you grow crops somewhere, you have officially colonised it”.

The castaway story has helped promulgate a view about human nature as eternal and unchanging. By taking human beings out of society, our supposedly fundamentally individualist survival instincts come to the fore.

However, the castaway story reflects on the relationship between individuals and society. A number of important questions arise from this relationship, including our place in nature, our autonomy as individuals, our ability to be collective and social, and the existence of different forms of power, inequality and domination.

The desert island story serves as an abstraction to think about what is “natural” in our interaction with others. On the island, would we fight or co-operate?

Triangle of Sadness and other modern castaway stories, reach back to one of the first English-language novels, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719). Today most people think of Robinson Crusoe as a children’s book and read it in a truncated edition with colourful cartoons of Robinson with a fur hat and a log canoe.

Robinson is overtly referenced in the works by many celebrated writers, including Alexander Pope, Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Dickens, Virginia Woolf, James Joyce and J. M. Coetzee. It might be a surprise, however, to learn that it is also one of the most referenced English language novels in the history of philosophy, appearing in works by philosophers as varied as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Karl Marx and Robert Nozick. It is still used as a classic example in economic textbooks to discuss fundamental principles of production and consumption.

More than a survival tale of a man shipwrecked on a desert island, Robinson Crusoe is also a fascinating moral fable of individualism. While many readers see the novel as showing human beings in an ideal state of nature, I argue the book can help shine light on capitalism as a social system.

Work and enslavement

The general plot of Robinson Crusoe is very familiar, but the details are often forgotten. For instance, only a portion of the novel happens on the island. Robinson’s adventure starts with his success as a merchant trading slaves, a character embodying the spirit of both the history of European colonialism and the new voracious drive of early capitalism. Robinson remains true to this spirit once he is shipwrecked, claiming the island to have “no society” and declaring the land as his personal kingdom.

Robinson becomes a farmer (using seeds from the shipwreck), raises cattle in accordance with European agriculture, hunts with muskets and hoards gold. In one of the most shocking parts of the novel, he captures and enslaves a man, who he calls “Friday”, converting him to Christianity. Much of the novel is about work. Robinson meticulously records his daily labour and Friday becomes an instrument of production for his master.

Robinson’s fear of others is confirmed with the presence of cannibals on the island. Luckily, Robinson is able kill a great number of the “savages” with his muskets. With the help of an English ship, he returns to England with Friday, his “most faithful servant”. Robinson has been on the island 28 years, two months and 19 days. But he sails again to Lisbon to recover the profit from his business ventures in Brazil, including slave plantations, before coming back to England. Defoe wrote a sequel, The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, in which Robinson and Friday return to the island, where Friday dies.

Many of the book’s early readers eluded the colonial theme, focusing on Robinson’s individual self-sufficiency. This is partly because of the historical context. Defoe lived a varied life as a merchant and political pamphleteer in the aftermath of the English Civil War, a revolutionary process started in 1642 and lasting until 1688.

The political contest between the Stuart monarchy and the powers of the English Parliament was interwoven with the development of capitalism, the proliferation of a commodity and wage-labour market and the growth of private ownership in agricultural production. Colonial expansion brought in bountiful resources and the slave trade developed.

The 17th-century was also one of the most significant in English political philosophy. The publication of Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan in 1651 and John Locke’s Two Treatises of Government in 1689 sought to offer political solutions to the new economic developments. In doing so, they helped establish distinctly modern conceptions of what it means to be an individual.

Hobbes thought human beings fundamentally individualistic. According to Leviathan, human beings in the “state of nature” are highly competitive, atomistic, war-like and motivated by fear. He argued that a strong political state would offer protection and he called this a “social contract”.

Locke followed Hobbes in his view that a social contract is the best model for individuals to form a society, focusing his attention on the justification of individual property rights. In his view, once human beings mix their labour with the natural world, we create private property.

Although scholars debate these issues, Hobbes supported colonialism and Locke justified the slavery of his time. Defoe was highly influenced by Hobbes and Locke, who provide the model individual for Robinson’s colonial adventure story.

Beyond individualism

Soon after its publication, Robinson Crusoe began its own adventure, appearing in crucial works of political and economic theory. By the middle of the 18th century, thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau identified the rising inequality of wealth as creating the ills of modern society. Rousseau envisaged a kind of democracy which allows for individuals to be free in their collective decision-making.

In Rousseau’s educational treatise, Émile (1762), initially Robinson Crusoe is the only book the young boy is allowed to read. Rousseau thought the novel provided a helpful picture of the solitary individual in the state of nature, where he can fulfill his “authentic” needs and desires, far from the corruptions of society. Although he does not discuss slavery, Rousseau uses the novel as a moral fable to contrast the inequalities of the modern world with an idealised state of nature.

In 1789, the French Revolution ushered in modernity. Hierarchies of birth and privilege were overthrown and liberty was proclaimed for all based on the equality of human beings. (Although as many critics, including Mary Wollstonecraft, pointed out this idea of equality was limited, and excluded women.) The age of political revolution inspired a revolution in thought. The depiction of slavery in Robinson Crusoe and the politics of individualism were called into question by G.W.F. Hegel. In Hegel’s philosophy, individuals were always part of social relationships and needed to be thought of in relation to communities.

If human beings are both individual and collective beings, I, for instance, require that others recognise me as a person who has value and I recognise others for their value. For a person to be free as a subject, Hegel thought there must be mutual recognition that we are free, together with political and social institutions allowing for recognition to be reciprocal. However, to recognise others collectively requires overcoming domination.

When teaching a famous section of his difficult, yet breathtaking, Phenomenology of Spirit (1807), Hegel used the example of Robinson Crusoe to dramatise a philosophical abstraction where recognition is not mutual. In his discussion of “mastery and servitude”, Hegel addressed the contradiction between the master who dominates the slave and makes them labour, but at the same time, desires a slave who respects their authority. In the enforcement of this power, the master denies the humanity of the slave, while also depending on their labour. In the novel, Robinson insists that Friday is his friend, but refuses to recognise Friday’s subjectivity, dominating him and gaining from his work.

Karl Marx dramatically challenged the politics of Robinson Crusoe. In Capital (1867), he pointed out that its assumptions about human nature should be examined historically. According to Marx, capitalism is not “natural”, but a social system brought into being by processes of force and colonial dispossession.

Even (apparently) alone on his island, Robinson’s character reflects modern class relations and capitalist economic principles. Marx analyses Robinson’s labour, pointing out that he behaves like a capitalist, despite working directly for his own survival. He acts as if he is producing commodities for the market, recording like a bookkeeper the time taken for his labouring tasks such as making tools, crafting a canoe, harvesting crops and rearing cattle. Robinson has the advantage of the instruments, ink and muskets salvaged from the shipwreck. He also goes to great pains to save the money from the wreckage despite it having no value on the island. He acts as if his survival depends on the market, not as one man in nature.

Although critical of Robinson Crusoe’s depiction of individual self-sufficiency, Marx uses the novel to consider human co-operation, asking the reader to “imagine, for a change, an association of free human beings, working with the means of production held in common”. Robinson’s self-directed labour, he argues, can help us think about the possibility of people socially co-operating, with the process and results of their work under their collective direction.

As Marx explains, labour under capitalism is inherently social since the goods and services we rely on are created by the work of many people over many discrete labour processes in one interconnected social system. No human being is an island.

However, the problem for Marx, is that this labour is mostly structured to accumulate profit for individuals. For Marx, co-operation allows for labour to serve social goods, decided not by market logic, but by human beings deciding what kind of society allows the best life. A “socialist Robinson” would be able to socially recognise the labour of others, not as a constraint to his freedom, but as an essential constitutive element. In Marx’s view, capitalism prevents human freedom.

Castaway stories are premised on the idea that the freedom of human beings is fundamentally as individuals. With the continued proliferation of such moral fables in films such as Triangle of Sadness, it can seem that self-interest is inevitable, contributing to the staggering inequality of today’s world.

However, when understood critically, Robinson Crusoe and its contemporary iterations illustrate the need for collective solutions and co-operation, in order to make our social relationships just. The achievement of human freedom for individuals can only be realised socially as the freedom of all. Only then can we truly rescue Robinson from his island.

Michael Lazarus, Dr Michael Lazarus teaches politics and philosophy at Monash University, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.