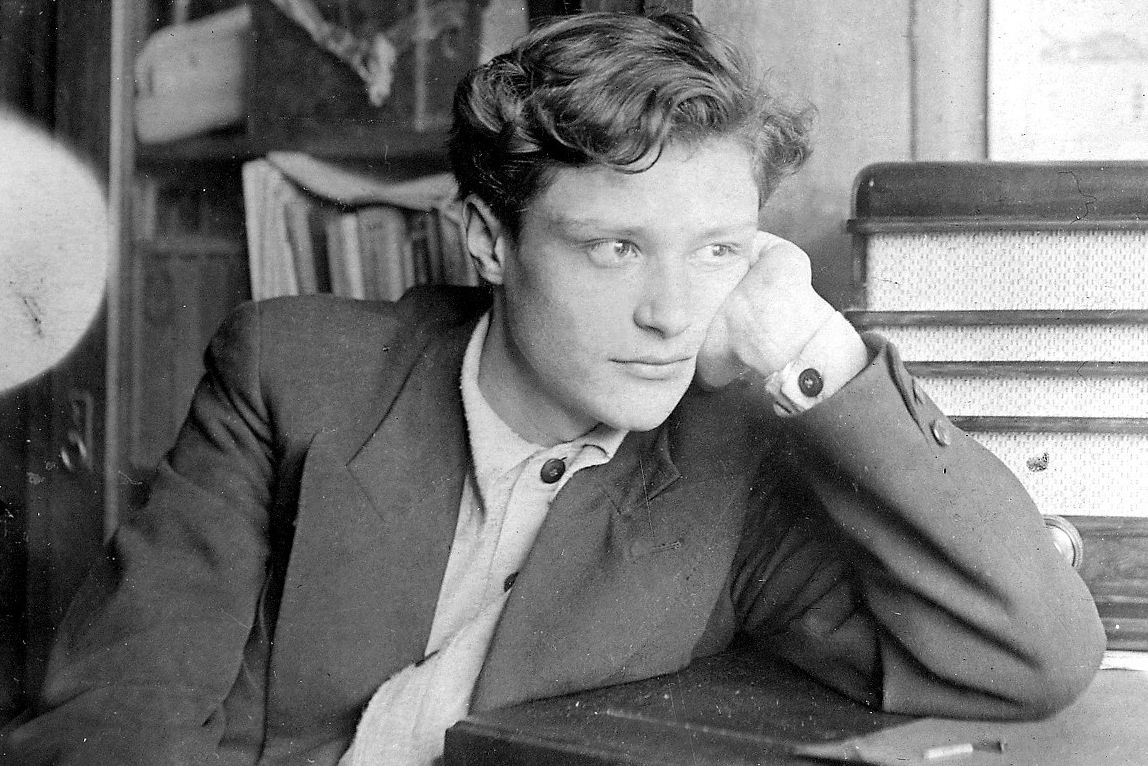

With the publication in Spanish of Corinna Lotz’s book on Ilyenkov, Ande publishing house has provided an excellent tool to the Spanish-reading public interested in Marxist philosophy.

Finding Evald Ilyenkov was the very first book that I have ever bought online. The book cost wasn’t high, but I also paid a similar amount for its shipment from the UK to Canada. Nothing to regret; it was a rewarding investment. It’s a short and easy-to-read book, but it addresses several key points of Ilyenkov’s life and thoughts that I judge to be of capital importance today, from both theoretical and political points of view.

First, the book highlights the difficulties and personal struggles that a philosopher, even a devoted Marxist like Ilyenkov, must endure in a socialist society such as the USSR. These difficulties started from the very beginning of Ilyenkov’s academic life when he was ultimately sacked from the Lomonosov University and prevented from teaching due to his ideas on the subject matter of philosophy and its proper relation to the sciences. The chapter of Lotz’s book entitled The Incendiary Theses covers this story adding to other published works on this topic like the well-documented commentary by Victor Carrion Evald Ilyenkov: Life and ideas[1] and David Bakhurst’s suggestive article Punks versus Zombies: Evald Ilyenkov and the Battle for Soviet Philosophy.[2]

In my view, Ilyenkov’s interpretation of the subject matter of philosophy as «the logic of the development of the world outlook»[3] is the correct interpretation of Engels’ remarks on the death and posthumous revenge of philosophy. However, what I think is most important about the «incendiary theses» story—and Lotz’s book really shows this aspect— is the comprehension of how harmful the absence of freedom of thought, and the subordination of philosophers to a clumsy class of bureaucrats standing above society, can be to Marxism.

I want to stress that the real problem here is not the peculiarities of a particular theory (in this case, about the subject matter of philosophy) but the coercive subordination of science by a bureaucratic establishment. The «orthodoxy» of Marxism in the Soviet Union and other socialist countries was never permanently attached to any peculiar theoretical content. “‘Marxism’ meant nothing more or less than the current pronouncement of the authority in question […]. You were a Marxist not because you regarded any particular ideas—Marx’s, Lenin’s, or even Stalin’s—as true, but because you were prepared to accept whatever the supreme authority might proclaim today, tomorrow, or in a year.”[4] To this, we should add the personal vendettas, opportunism, and generational struggles within the academic circles using political influence and ideological accusations as their weapons. As the Cuban saying goes, “one day they could pay you a homage, and at the next an act of repudiation.”

Ilyenkov continued being tormented by these clumsy bureaucrats all his life. Some of his works were published and even translated into other languages, and he was awarded important academic prizes. However, he also suffered professional persecution, censorship, and unjust rejections from many important Soviet journals. You could imagine how difficult it was for Ilyenkov to remain faithful to himself while developing his original views on philosophy, dialectical method, and the ideal. Nevertheless, he delivered profound philosophical work in his short but prolific life.

However, the core of Lotz’s book is not just Ilyenkov’s life and work but rather about the story of his reception in the West, particularly in the English-speaking world. I think that this is indeed the most exciting part of the book. While reading it, it occurred to me that it might be an interesting exercise to reflect on how each of us came across this thinker in our different countries. That’s why I won’t try to summarize the story of Ilyenkov’s reception in the English-speaking world; I encourage the reader to learn about it directly from Lotz’s book.

Instead, let me share with you how I encountered Ilyenkov while I was an undergraduate student at the University of Havana.

Back in 2010, the five-year Bachelor’s degree program in philosophy at the University of Havana included (it may still include today, I’m not 100% sure), in the second semester of its second year, a course entitled Thought and Spiritual Production. The main text of this course was Ilyenkov’s Dialectical Logic. It is indeed an exciting and different book, and soon enough, it was filled with highlighting ink of different colors, hundreds of marginal annotations, book stickers, self-made topic indexes, and so on.

As Gilberto Perez Villacampa said: “Ilyenkov’s book is one of those that refuse to stay on the shelf at home and less in the library; it’s one of those that require—as Nietzsche wanted for his own—the capacity to ruminate on them once ingested, one of those that lose their covers after many readings and constant handling in places less than ideal for reading.”[5]

After my graduation, I became a professor at the same university and gave that course myself. I remember that in those days, I tried to complement Ilyenkov’s ideas in Dialectical Logic and other texts with the work of an extraordinary Cuban philosopher, Zaira Rodriguez Ugidos.

Nonetheless, the text that made me fall in love with Ilyenkov’s thought was far more modest than Dialectical Logic, both in length and in its theoretical depths. It was his article entitled «Our schools must teach how to think.» When I first read this article, I felt somewhat jealous: I felt like that was precisely how I saw things, but Ilyenkov wrote it first.

Lotz’s book, especially in its discussion about the Zagorsk experiment, also addresses the key role assigned by Ilyenkov to the formation of a highly developed personality and the ability to think independently. Let me share my take on this important topic because I believe it is of the most urgent relevance.

The transition from the formally “collective” to the real, genuine, directly collective property in a truly horizontal democracy confirmed by universally developed individuals was Ilyenkov’s life purpose

For Ilyenkov, learning materialist dialectics through a critical examination of the history of human thought, particularly philosophy, is equivalent to learning how to think correctly at a theoretical level. On the educational plane, this means that the schools should teach the individuals not what to think (i.e., what they are allowed to think and repeat like a parrot) but how to think (i.e., how to think independently). And this is a vital aspect of the communist project. For the problem of the formation of an all-rounded personality, in Ilyenkov’s words, “the task of transforming every individual on Earth into a highly developed and universal individual”[6] is not just an educational endeavor but a political one —its the final and decisive emancipatory milestone in the human quest for freedom. For “only a community of such individuals will no longer need an “external”— “alienated”—form of regulation of its activities—in money-commodity, legal, state-political and other forms of people management.”[7] Only a community of independently thinking individuals can truly appropriate the social wealth without the formal intermediary of a “vanguard,” i.e., a class of professional bureaucrats.

The transition from the formally “collective” to the real, genuine, directly collective property in a truly horizontal (not «centralist,» i.e., vertical) democracy confirmed by universally developed individuals was Ilyenkov’s life purpose. Tragically, the systematic frustration of that hope in the “stagnated” Soviet bureaucratic regime submerged Ilyenkov into a depressive crisis that eventually led to his suicide.

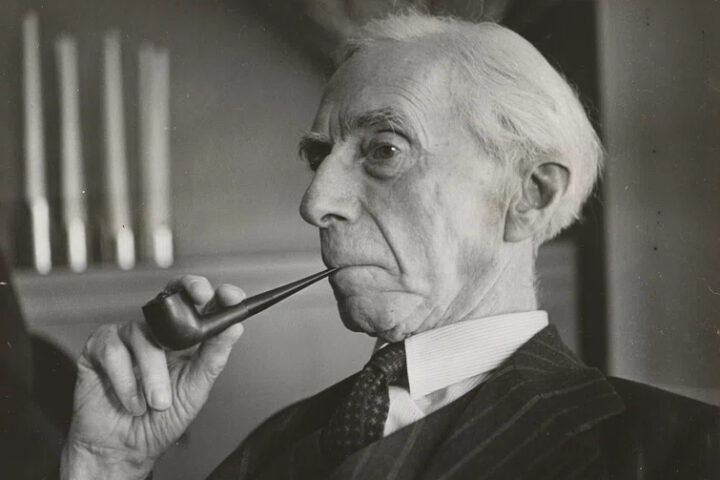

I believe that we must take Ilyenkov’s tragic death seriously. It might sound exaggerated, but I believe that an analogy with the death of Socrates could be helpful here.

Concerning Ilyenkov and socialism, we must assume Plato’s role regarding his mentor and the Athenian democracy. We must explain how the supposed more rational (socialist) society led his most advanced thinker to suicide. We must critically uncover how and why such tragedy was possible—if not inevitable— in a socialist country.

Plato’s entire work can be seen as his attempt to explain how the peak of civilization, the light of human Reason in the ancient world, the democratic Polis of Athens, killed its most rational citizen. It became clear in the eyes of Plato that there was something wrong with this society for which his mentor had lived and died, and he became his most profound critic. Concerning Ilyenkov and socialism, we must assume Plato’s role regarding his mentor and the Athenian democracy. We must explain how the supposed more rational (socialist) society led his most advanced thinker to suicide. We must critically uncover how and why such tragedy was possible—if not inevitable— in a socialist country. Without any attempt to hide or diminish uncomfortable truths, we must identify what is wrong with socialism.

With this, of course, by no means do I suggest assuming Plato’s proposal, that is, the construction of an aristocratic form of communism. Ilyenkov himself was aware that that kind of elitist communism was, in fact, the problem in his country. Here is what he said about it:

[Marx rejects] Plato’s dream. Such an idea is unacceptable for Marx because it presupposes the right of the State—like some kind of impersonal monster—to indicate what each individual must do and how to do it without taking into account their desires […]. Because in practice, the right to manipulate individuals is monopolized by a caste of official bureaucrats, who impose their clumsy will on the whole society and picture their limited intelligence as the Reason, as the embodiment of «general» (collective) reason.[8]

This quote is from Ilyenkov’s fascinating text Of Idols and Ideals. This text was recently published in Spanish in a three volumes collection of Ilyenkov’s works by a Spanish publishing house named «Dos Cuadrados.» I was delighted to see that it also includes the text «Hegel and alienation.» These two texts are essential because they contain one aspect of Ilyenkov’s thought widely overlooked in the West, especially in the English-speaking world: Ilyenkov’s political thought and, particularly, his views on the problem of alienation.

For Ilyenkov, the most primitive form of alienation is idolatry, to the extent that he identifies it as a non-human specific (i.e., animal) form. He uses the example of an experiment by Pavlov in which the great physiologist observed that once created the positive conditioned reflex by lighting a bulb before serving food to the dog, the animal eventually started licking the bulb when it was turned on. The animal psyche could not separate the symbol (signal) from what it represents, attributing to the former the properties of the latter. And we must admit that the leftish, particularly in Latin America, have been licking many bulbs for far too long: the «revolutionary leaders» have been turned into unquestionable idols, the communist ideal has turned into a cult with its sacred items of faith, we have made offerings and altars to the «heroic Guerrillero» and prayed a «Chavez ours» with blind devotion.

In the name of the idol of «communism, » we have justified the most despicable injustices and the unnecessary suffering of entire peoples. This fanatic and sectarian attitude prevented us from performing our Platonic critique to find out what has been going terribly wrong with socialism in the past and the present centuries.

Unlike some Western Marxists who addressed this topic, treating it as an essentially mental (i.e., subjective) phenomenon, Ilyenkov has a concrete, objective, and earthly conception of alienation. I would like to leave the reader with a quote from Ilyenkov that illustrates this and that I find of a vital importance today due to the unjust and dangerous Russian invasion of Ukraine:

[The elimination of alienation] is a problem that involves the creation in the entire Earth globe (and on a smaller scale, this problem is impossible to solve) of conditions that exclude the apparition of wars forever. For in the current circumstances, war is the perspective of the real loss for humankind of all the material and spiritual culture achieved by her, of the “alienation” of this culture in the literal and crude sense of the word. The possibility of war is the possibility of “losing our lives.” And this—sadly—is not a mere game of words.[9]

Bibliography

Bakhurst, David 2019, ‘Punks versus Zombies: Evald Ilyenkov and the Battle for Soviet Philosophy’, in Philosophical Thought in Russia in the Second Half of the 20th Century: A Contemporary View from Russia and Abroad, edited by Vladislav A. Lektorsky and M. Bykova, pp. 53–78, London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Carrión, Víctor Antonio 2017, ‘Evald Iliénkov: vida e ideas’, in Dialéctica de lo abstracto y lo concreto en “El Capital” de Marx, edited by Evald Vasílievich Iliénkov, Quito: Edithor.

Iliénkov, Évald V. 2021, ‘Hegel y el problema de la enajenación’, in Obras Escogidas, Vol. 2, pp. 289-306, Madrid: Dos Cuadros.

Iliénkov, Evald Vasílievich 1997, ‘De ídeolos e ideales’, Contracorriente, 10.

Ilyenkov, Evald V. 1977, Dialectical Logic: Essays on its History and Theory, translated by H. Campbell Creighton, Moscow: Progress.

Ilyenkov, Evald V. 1991, Filosofiya i kul’tura, [Philosophy and Culture], Moscow: Politizdat.

Kołakowski, Leszek 1978, Main Currents of Marxism: Its Rise, Growth, and Dissolution, Vol. 3. The Breakdown, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Pérez Villacampa, Gilberto 1996, ‘Iliénkov in memoriam’, Contracorriente, 2, 3: 59-74.

Notas

[1] Carrión 2017.

[2] Bakhurst 2019.

[3] Ilyenkov 1977, pp. 251, 372.

[4] Kołakowski 1978, p. 4.

[5] Pérez Villacampa 1996, p. 59

[6] Ilyenkov 1991, p. 151.

[7] Ilyenkov 1991, p. 151.

[8] Iliénkov 1997, p. 78.

[9] Iliénkov 2021, p. 305-306.